Of course, I couldn’t begin this without a mention from the master of the Dark-Side.

This creature is one of my most favourites in all fairytales which I have swallowed at an early age as a child and still onto now! The Div (Demon) in old Persian fairytales have a great presence and unusually as a man might expect, for me, they were very interesting! Their essential came from Gnome or as Irish folklore leprechaun.

As I remember it was almost normal to see such creatures in the bathrooms or elsewhere.

And Yes! They play a huge role in the Persian fairy tales, of course, I’m not talking about the “Thousands and one night”, there are so many more fairy tales of that kind in our history.

Though, in the time as a child; for us two (Al, my brother and me) our parents had no time to read out or aloud these wonderful stories for us. We had to get used to reading them by ourselves. And we were just hungrily got them in.

I found here some interesting different name for this subject.;

The Infernal Names

Abaddon—(Hebrew) the destroyer.

Adramalech—Samarian devil.

Ahpuch—Mayan devil.

Ahriman—The Mazdean devil. (This is in old Perian culture as mighty as the God-self; Ahuramazda: The Duality.

Amon—Egyptian ram-headed god of life and reproduction.

Apollyon—Greek synonym for Satan, the archfiend.

Asmodeus—Hebrew devil of sensuality and luxury, originally “creature of judgment”(? 😮😉😅) via: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_infernal_names

To be shared is here a nice article about the way of the “Imagination of this creature”. Let see and read. 💖🙏

The Foot-Licking Demons & Other Strange Things in a 1921 Illustrated Manuscript from Iran

Few modern writers so remind me of the famous Virginia Woolf quote about fiction as a “spider’s web” more than Argentinian fabulist Jorge Luis Borges. But the life to which Borges attaches his labyrinths is a librarian’s life; the strands that anchor his fictions are the obscure scholarly references he weaves throughout his text. Borges brings this tendency to whimsical employ in his nonfiction Book of Imaginary Beings, a heterogenous compendium of creatures from ancient folk tale, myth, and demonology around the world.

Borges himself sometimes remarks on how these ancient stories can float too far away from ratiocination. The “absurd hypotheses” regarding the mythical Greek Chimera, for example, “are proof” that the ridiculous beast “was beginning to bore people…. A vain or foolish fancy is the definition of Chimera that we now find in dictionaries.” Of what he calls “Jewish Demons,” a category too numerous to parse, he writes, “a census of its population left the bounds of arithmetic far behind. Throughout the centuries, Egypt, Babylonia, and Persia all enriched this teeming middle world.” Although a lesser field than angelology, the influence of this fascinatingly diverse canon only broadened over time.

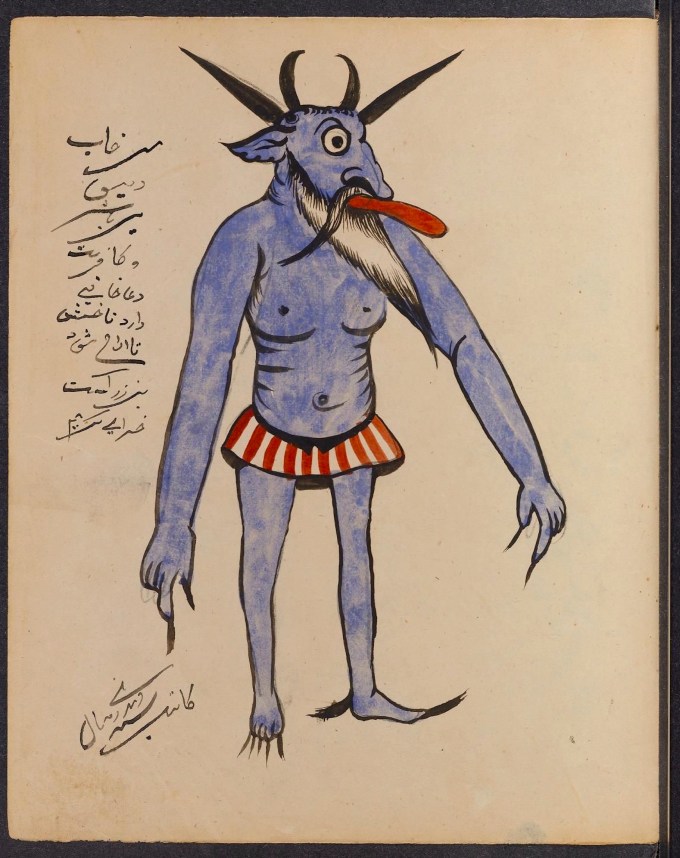

“The natives recorded in the Talmud” soon became “thoroughly integrated” with the many demons of Christian Europe and the Islamic world, forming a sprawling hell whose denizens hail from at least three continents, and who have mixed freely in alchemical, astrological, and other occult works since at least the 13th century and into the present. One example from the early 20th century, a 1902 treatise on divination from Isfahan, a city in central Iran, draws on this ancient thread with a series of watercolors added in 1921 that could easily be mistaken for illustrations from the early Middle Ages.

As the Public Domain Review notes:

The wonderful images draw on Near Eastern demonological traditions that stretch back millennia — to the days when the rabbis of the Babylonian Talmud asserted it was a blessing demons were invisible, since, “if the eye would be granted permission to see, no creature would be able to stand in the face of the demons that surround it.”

The author of the treatise, a rammal, or soothsayer, himself “attributes his knowledge to the Biblical Solomon, who was known for his power over demons and spirits,” writes Ali Karjoo-Ravary, a doctoral candidate in Religious Studies at the University of Pennsylvania. Predating Islam, “the depiction of demons in the Near East… was frequently used for magical and talismanic purposes,” just as it was by occultists like Aleister Crowley at the time these illustrations were made.

“Not all of the 56 painted illustrations in the manuscript depict demonic beings,” the Public Domain Review points out. “Amongst the horned and fork-tongued we also find the archangels Jibrāʾīl (Gabriel) and Mikāʾīl (Michael), as well as the animals — lion, lamb, crab, fish, scorpion — associated with the zodiac.” But in the main, it’s demon city. What would Borges have made of these fantastic images? No doubt, had he seen them, and he had seen plenty of their like before he lost his sight, he would have been delighted.

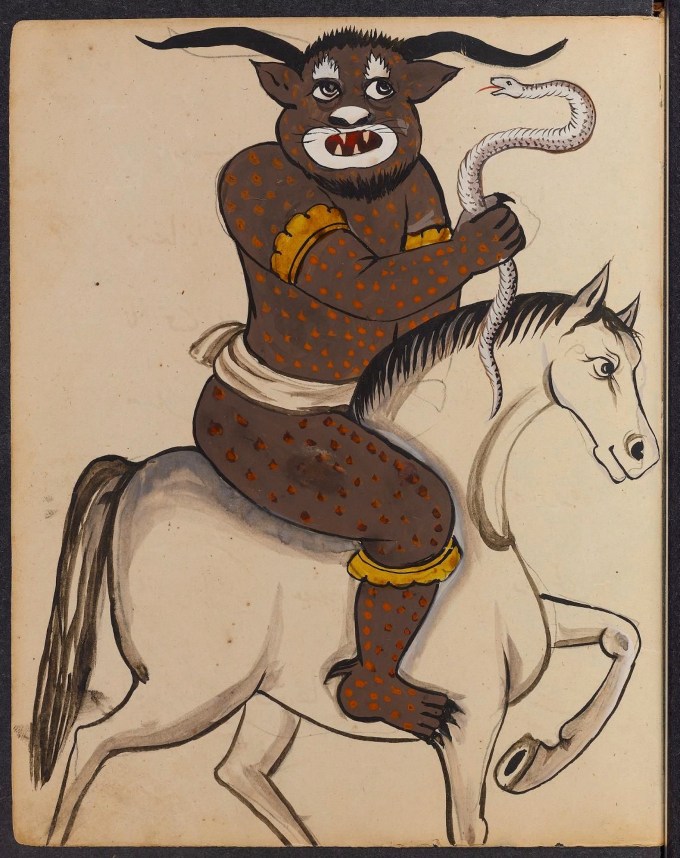

A blue man with claws, four horns, and a projecting red tongue is no less frightening for the fact that he’s wearing a candy-striped loincloth. In another image we see a moustachioed goat man with tuber-nose and polka dot skin maniacally concocting a less-than-appetising dish. One recurring (and worrying) theme is demons visiting sleepers in their beds, scenes involving such pleasant activities as tooth-pulling, eye-gouging, and — in one of the most engrossing illustrations — a bout of foot-licking (performed by a reptilian feline with a shark-toothed tail).

There’s a playful Bosch-ian quality to all of this, but while we tend to see Bosch’s work from our perspective as absurd, he apparently took his bizarre inventions absolutely seriously. So too, we might assume, did the illustrator here. We might wonder, as Woolf did, about this work as the product of “suffering human beings… attached to grossly material things, like health and money and the houses we live in.” What kinds of ordinary, material concerns might have afflicted this artist, as he (we presume) imagined demons gouging the eyes and licking the feet of people tucked safely in their beds?

See many more of these strange paintings at the Public Domain Review.